About World Languages

LEARNING LANGUAGE

The need to know a foreign language in the United States is as old as the country itself. Language education in the United States has historically involved teaching English to immigrants to the United States and, conversely, teaching Spanish, French, Latin, Italian, German and more to native English-speaking students within the country. There have been periods in our nation’s history where the learning of another language have been especially needful and arguably invaluable to the strengthening our nation’s human capital. For example, after World War II, Japanese language education increased and following the reformation of the People’s Republic of China, Chinese language education experienced unprecedented growth. There are countless other historic and modern examples of current events that necessitate and sometimes unexpectedly precipitate renewed interest in teaching and learning a second language.

Foreign language education in the United States, particularly at the K-12 level, continues to experience dynamic changes in terms of enrollment numbers and the locations of programs and program designs. Unfortunately, no matter the perceived benefits of knowing a world language, and the volume of scholarly research to support world language education, budgetary decisions and staffing issues continue to eliminate or consolidate programs.

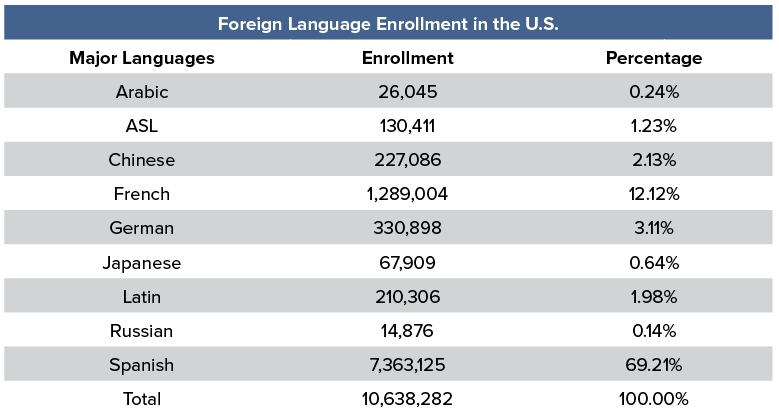

At present, approximately 20 percent of the K-12 population in the United States is enrolled in foreign language courses (2017).

LEARNING CULTURE

The World-Readiness Standards for Learning Languages were created by the American Council for Teaching Foreign Languages (ACTFL) as a roadmap to guide learners to develop competence to communicate effectively and interact with cultural competence to participate in multilingual communities at home and around the world. The World-Readiness Standards for Learning Languages define the central role of world languages in the learning career of every language student. The five goal areas of the Standards establish an inextricable link between communication and culture, which is applied in making connections and comparisons and in using this competence to be part of local and global communities.

As the main premise of its Vision statement, ACTFL “envisions an interconnected world where everyone benefits from and values a multilingual and multicultural education” (2025). ACTFL is the largest membership community of language education professionals passionate in the United States and the aim of the organization is to expand cultural richness and diversity at all levels of education.

Source:

American Councils for International Education, American Council for the Teaching of Foreign Languages, Center for Applied Linguistics: The National K-12 Foreign Language Enrollment Survey (2017)

Source:

American Councils for Teaching Foreign Language, World -Readiness Standards for Language Learning: The Roadmap to Language Competence (2021)

It is important to note here that my proposed R.E.A.C.H. model hinges on the understandings of intercultural competence as first defined by Michael Byram in 1997. His conceptualization of Intercultural Competence (ICC) challenges more traditional notions of communicative competence (CC), which were historically prevalent - and largely still are - in world language education.

Essentially his argument is that curriculum and instruction efforts that only emphasize and elevate “the ideal native speaker” create a target learning objective which is in fact impossible for the language learner to ever achieve. This invariably positions world language education in a deficit-based paradigm. This is particularly obvious in and most especially problematic in the K-12 educational system in the United States where many advanced world language learners - no matter how ‘gifted’ or ‘creative’ they may be - are realistically never going to be able to achieve or maintain native-speaker proficiency. And, moreover, because of the overemphasis on reaching an impossible ideal, many gifted and creative learners miss opportunities to have other perhaps more impactful types of skill development.

In his work, Byram instead values the qualities of a competent intercultural speaker. He described these qualities as a set of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and dispositions that can be cultivated with updated and intentional teaching and learning methods inside the world language classroom. His work goes on to specify these qualities:

Savoir: knowledge of self and other; of interaction; individual and societal

Savoir être: attitudes; relativizing self, valuing other

Savoir comprendre: skills of interpreting and relating

Savoir apprendre/faire: skills of discovering and/or interacting

Savoir s’engager: political education, critical cultural awareness

Byram’s Model of Intercultural Competence

(Byram, 1997)

“It’s not that foreign language teachers are the only people who can

develop intercultural competence. Historians – it’s part of what they do. And in that sense historians

are developing ICC but not in the sense of

cultural behavior training unless you are going in a time machine and go back and meet

people!

I think across the curriculum there are opportunities, just as across the curriculum

there are opportunities for language development.”